It’s true what they say: Everything’s bigger in America… our cars, our meals, and even our little craft breweries.

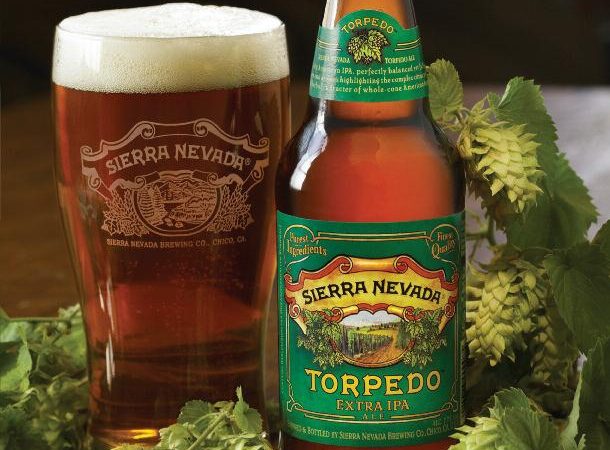

The largest craft brewer in the United States, according to the Brewers Association, is the Boston Beer Company, maker of Samuel Adams. It sold about 2.4 million U.S. barrels in 2011. Sierra Nevada is the second-largest with 2012 production of 1 million barrels.

This begs an obvious question: Why are plants that churn out millions of barrels of beer, with marketing departments and armies of sales reps, still considered “craft” in the United States?

It’s a question that’s been beaten into the ground among American geeks, beer writers and industry types.

“In this state of flux, every few years a heated kerfuffle erupts about the nature of craft beer, and who can belong to the club of those who brew it,” wrote Julie Johnson, co-owner and contributing editor of All About Beer magazine, in a recent column. “It’s an argument about economics, dressed up to look like something nobler.”

Yet it merits a fresh look as breweries using that C-word – or the A-word artisanale, or any number of translations – make inroads in countries around the world. The modern movement toward more characterful beer is an international one, and in different countries and times its participants react to different circumstances. In the U.K., the Campaign for Real Ale reacted not just to a loss of flavour but a loss of tradition. So CAMRA had to define that tradition.

In the U.S., craft brewers reacted to a monotonous marketplace dominated by companies of massive size. The Brewers Association serves and is comprised of “craft” brewers, so it has a certain pragmatic need to define what that means. That definition is a product of the group’s history and issues that have faced American brewing – notably, taxes. The short version of the Brewers Association definition is three words long: small, independent, traditional. The fun is in unpacking what those words mean.

To get the latter two out of the way:

“Independent” keeps out breweries with a large chunk – 25 per cent or bigger – owned by noncraft (i.e. giant) breweries. That keeps out smaller brewers who sell out to the big guys.

Article continues in Beers of the World Magazine Issue 27