What is a hop?

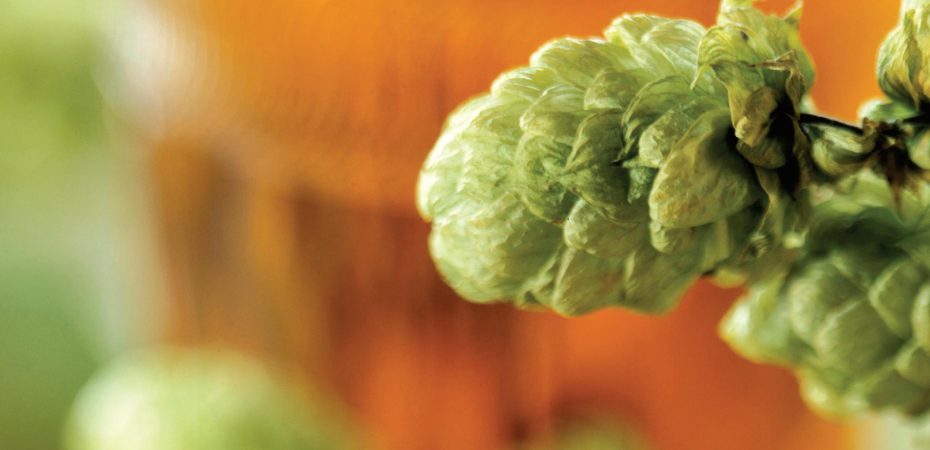

The hop is a wild, sprawling plant – humulus lupulus in Latin, meaning wolf plant, so-named because the Romans said it grew wild among willow trees like a wolf among sheep – tamed by hop farmers by training it round poles to give it the best access to the light. The hop flower, or cone, contains oils and acids that help to give flavour, aroma and stabilising qualities to beer. After harvesting, hops have to be dried to prevent them becoming affected by mould and to enhance their floral aromas, traditionally done in the United Kingdom in conetopped oast houses.

Where do they grow?

With its rural landscape dotted by oast houses (once used for drying hops but now almost universally converted to the kind of houses you see in Sunday supplement ‘interiors’ sections), Kent is usually thought as the main hop area of Britain.

These days, the oast houses all have fund managers living in them, and Kent has even lost the honour of being the hop capital of the United Kingdom to Herefordshire in terms of hop farm acreage. Hereford, Worcestershire and Kent account for around 95 per cent of UK production. Sussex, Suffolk and Surrey have relatively small levels of hop production. In Europe, Bohemia in the Czech Republic and Hallertau in Bavaria, Germany, are among the most important, while Washington State is the United States’ hotbed.

What’s their significance to beer?

Hops are usually added to beer to provide flavour or aroma. For flavour, they provide a sharp bitterness that’s favoured by the British palate, while for aroma hops generally give a zesty, floral character.

Hops also help to give beer stability, acting as a kind of natural preservative. One of the most common bitter beer styles is India Pale Ale (IPA). This was originally beer shipped to British troops in India, with extra doses of hops added to help preserve the beer on its journey by sea. The beer style stuck in its own right after the collapse of the British Empire, and Greene King’s IPA is arguably the best known example of the style.

Hops are added to beer in one of three forms. The first is simply adding whole hops. The second is hop leaves pressed into pellet form, basically a way of making them easy to transport. The third is hop oils or extracts.

Hops are generally added to the kettle or copper during the boiling of the wort (the heated water and malt mix that is created in the first stage of the brewing process). In some cases, a proportion of hops are held back until near the end of the boiling process to give an extra hop aroma, a process known as late hopping.

Some brewers use a process called dry hopping, to give their own distinctive quirks to ales, by adding a small dose of hops to the beer once it has been put in cask.

More rarely, beers are made with what are called green hops, those plucked straight from the plant, or bine, without being dried first.

What do different hop varieties do?

Like grapes for wine, there are dozens of different varieties of hops, and there are particular varieties that are more likely to be found in certain places. Like grapes, different varieties of hop have different attributes.

Broadly speaking, hops can be divided into two styles: aroma hops and flavour hops, that is those that bring a particular floral hoppy aroma to beer, and others that influence the taste.

As well as imparting bitterness, hops may also give other flavours such as fruitiness or spiciness.

The bitterness comes from the alpha acid content of the hops. This varies from harvest to harvest, but some varieties have generally higher alpha acid content than others.

In British beer, Target, Admiral and Phoenix have particularly high alpha acid contents, and are therefore tied to bitter characteristics in beer.

Fuggles, Goldings and Progress have relatively low alpha acid contents and are used mainly for aroma.

As wine has a collection of “noble” grape varieties (including Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling), so too there are noble hops. These are the continental varieties Hallertauer, Spalt, Mittelfruh, Tettnanger and Saaz, used principally by German, Belgian and Czech brewers for many centuries.

Each of these is a low bitter hop which is why bitterness tends to be a style associated with British ales rather than continental lagers. The native Czech variety Saaz, for example (sometimes referred to by its German name Zatec) has one of the lowest alpha acid contents of all, less than a quarter of the British variety Admiral, and is widely used in pilsner-style lagers.

In one way, the high bitterness of hops from British farms has brought about the UK hop industry’s relative decline in recent years. The more bitterness they can provide the fewer hops you need to achieve a balanced and accessible flavour. The growing popularity of lager has put extra pressure on the industry.

Goldings, Fuggle and First Gold are the most heavily planted styles in the UK, though the areas used for the first two of these, plus Target and Challenger, have been in steep decline in recent years.

Admiral has emerged as a new favourite because of its high alpha acid content which means it delivers more for less expense on raw materials and transport. First Gold, and other “dwarf” hops such as Herald and Pilot, are in demand because they are easier to harvest and, therefore, less costly. Although there are single varietal beers on the market, most brewers use a combination of varieties to reap the benefits of different hops’ qualities.

Article is from Beers of the World Magazine issue 1